“Port Hope is a remarkably picturesque community located along the shores of Lake Ontario.”

This statement provides the introduction to Port Hope’s Facebook page. Characterized by a natural landscape of deep ravines, tall trees, a winding river, and Lake Ontario views coupled with a built environment of fine 19th century commercial buildings, residences, churches, and country houses, designed to enhance that natural landscape, Port Hope is indeed “remarkably picturesque.”

Peter Stokes stated that Walton Street “set Port Hope apart from so many other towns” because it was the “finest formal 19th century streetscape of southern Ontario.” As new research into picturesque landscapes is indicating, the fact that this focal avenue along with Port Hope’s other heritage streetscapes, neighbourhoods and rural areas exist within our picturesque natural landscape makes Port Hope into a unified whole that is unlike any other. Retaining this and building upon it, as new development necessarily occurs, becomes our challenge, and our ACO Advocacy members have become convinced that the planning for such initiatives as the Walton St. Reconstruction and the Waterfront/Riverwalk enhancements needs to be integrated within an overarching vision for the town.

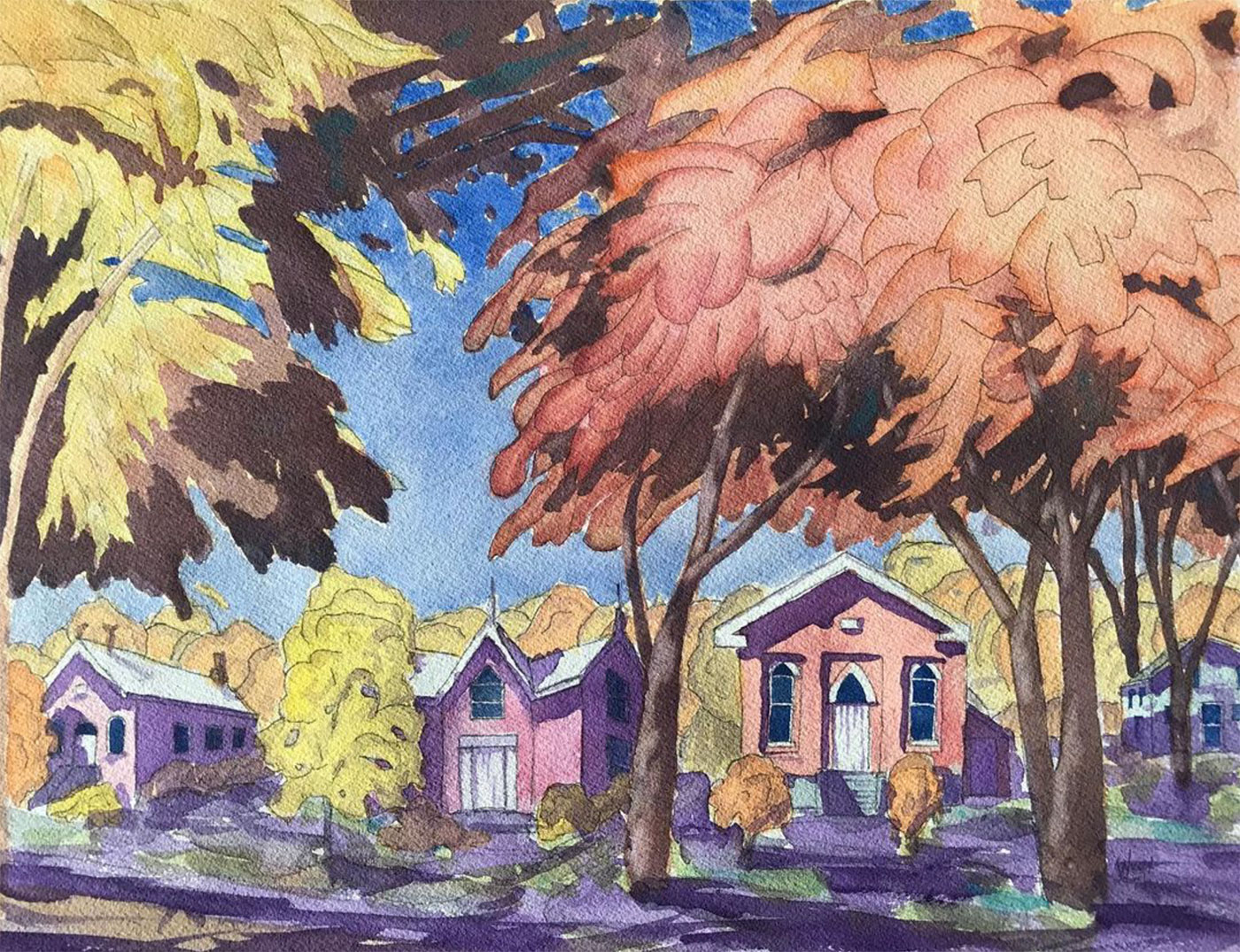

The ideas behind the Picturesque movement emerged in England during the 18th century. A landscape was considered picturesque if it was irregular, varied, and intricate, perhaps with an uneven configuration of tall trees causing ever-changing effects of light and shadow, ravines and rocky slopes, or a stream rippling over rocks. When architectural elements were added, they needed to be designed and situated in such a way as to be appropriate to that setting. Port Hope’s plethora of parapet walls, church steeples, towers, belvederes, and pinnacles, silhouetted against the sky along streets and roads that curve, rise and fall would have been deemed particularly well suited to be termed a picturesque setting.

The proponents of Picturesque ideas would not have believed that such interspersed elements on their own were sufficient. The idea was always to ask the question: Do these elements reflect an appreciation for the integration of architecture and landscape, a concern for how a structure rests upon its site, and a belief in creating a setting in which both the built and natural landscapes are improved by these elements?

This means that contemporary elements and new purposes may be appropriate within an evolving picturesque landscape and that the ideas behind Picturesque Aesthetics may continue to resonate today. Susan Herrington, an Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture at the University of British Columbia, notes in her article, Framed Again: The Picturesque Aesthetics of Contemporary Landscapes, that because certain aspects of picturesque works may awaken associations that evoke “sensations, ideas, and memories,” Picturesque ideals can provide “a useful concept for understanding the growing appreciation for parks that recycle former industrial sites.”

Old ruins were often left to decay and become overgrown within picturesque landscapes because advocates believed they would not only enhance the appeal of the setting but also induce in the viewer feelings such as nostalgia and wonder. Today, the ruins of industrial structures that have fallen into disuse may also be “enjoyed as picturesque.” Herrington cites, among others, the example of Duisburg North, the former site of the Thyssen factory in Germany, now cleaned up and transformed as a park, stating that it demonstrates “that the structures of the industrial age were now distant enough in time and memory to serve as ruins whereby a chain of associations could be released.” The park was designed by Peter Latz, “with the intention that it work to heal and understand the industrial past rather than reject it,” and, according to Herrington, the abandoned railway scaffolding, blast furnaces, and foundry walls now summon “musings upon the loss of the Ruhr Valley’s industrial might to overproduction, pollution, and foreign competition.”

This is not to say that more light-hearted pursuits should not also be included in such a landscape. As Herrington notes, the activity programs at Landscape Park Duisburg Nord “surprise both the eye and the intellect.” In addition to hiking trails and cycle paths, there is a large indoor diving centre housed in the gasometer, a series of challenging climbing walls on the ore bunker site and a group of popular event spaces in the steam blast house, the foundry and the power station.

It seems then, that Picturesque aesthetics require us to give serious thought to whether or not any changes we are about to make in Port Hope will improve our picturesque landscape. They also require us to consider seriously what has been left behind from the past. For example, retaining some of our industrial relics such as the Nicholson File Factory, if it cannot be fully restored, as a structure like the Brickworks in Toronto’s Don Valley, or the railway bridge remnants from two railways as overgrown “follies,” could provide echoes of Port Hope’s past along side a newly added pedestrian bridge across the river.

Thus, care must be taken in what we choose to do with Port Hope’s exceptional landscape. In her article, Herrington states that asking residents which environments they like and then offering a wish list of items from which they may choose was the 20th century approach to public landscape design. She notes, however, that this approach could be very limiting and suggests that a more relevant and searching question might be: “How are people moved by landscapes and how might landscapes activate a rich range of human experiences?”

Port Hope’s picturesque landscape is moving and rich because it binds architecture and nature; urban and rural; past and present. Let us care for its entirety as we contemplate future innovations.

Photo: Wesleyville by Wrex Roth. Proponents believed that a picturesque landscape should be interesting enough for an artist to paint.