By Bruce Bowden

They sacrificed for us. It’s our turn to save this important building, so they are never forgotten.

“Everybody Here Says the Hospital Campaign is the greatest thing that has come to Port Hope since Confederation.”

Wm. Thorndyke

This was the sentence typed on subscription cards for residents of Port Hope to donate money to hospital trustees for the first public hospital of Port Hope. One such card, now in the Port Hope Archives, pledged $100 over four payments from January to July 1911, from Wm. Thorndyke of 108 Princess St., Port Hope, signed Dec. 24, 1910, Christmas Eve.

Establishing a public hospital to serve Port Hope and area residents was a vast undertaking. There were town council and hospital committee meetings. There were letter-writing campaigns and outreach to solicit funding. There was a major fundraiser at the Royal Opera House on Walton Street, located above the former Royal Bank building. People rallied together to raise the money and support to make it happen.

It’s the story of a community with spirit, drive and determination.

Now it’s our turn. With the historic buildings under threat of demolition, we can step up and stand our ground. The former hospital buildings at 65 Ward St. treated more than 200 WW1 soldiers and served as a significant recuperative centre for soldiers and veterans during and after the war. The original hospital became a nursing school that trained ambitious women from across the province, giving them skills crucial to the war effort and well beyond to practice in the medical field.

The story of the Port Hope Hospital is a one of sacrifice and a commitment to see things through.

Our first public hospital began with the efforts of dedicated women who went on to become the founders of the Ladies’ Hospital Mission. They set a goal of $20,000 – a substantial sum at the time. Then the first public meeting to promote the idea of a hospital for Port Hope was held on Apr. 28, 1911, and an executive committee were appointed to handle subscriptions to fund such a project.

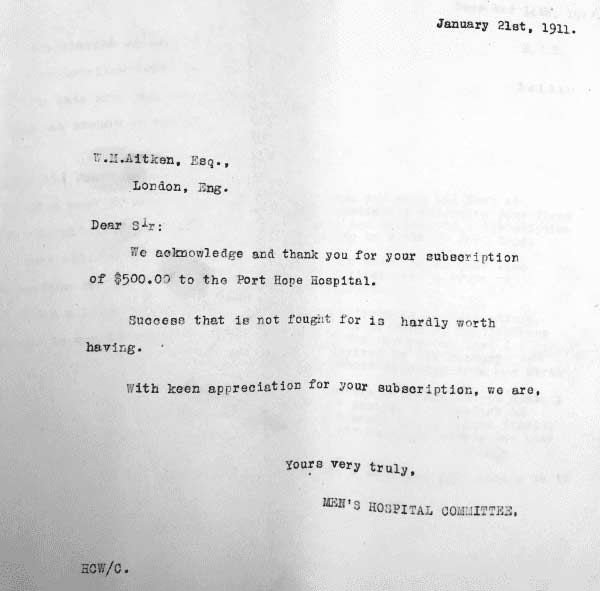

A Men’s Hospital Committee was formed to solicit funds from known philanthropists and men’s organizations at home and abroad. As the Committee proclaimed on Jan. 21, 1911: “Success that is not fought for is hardly worth having.” There are subscription letters of the Committee’s success in the Port Hope Archives. The fight was worth the reward.

One favourable location site for the hospital was the Janes’ two-an-a-half-acre lot at the corner of Hope and Ward streets. The price of the lot was $5,000 of which $1,000 was returned to the hospital by the Janes family as a donation.

The west boundary was Princess Street and the south, private property, which included a two-storey brick house on Hope Street. It was the former home of Colonel William McLean who owned a piano and organ business in town. One of his three sons later gave $25,000 to the Port Hope Hospital.

The architect who inspected the property suggested that the house could be renovated as a temporary hospital until the new one was completed. The work was done and the nine-bed hospital opened in January 1913 with a medical staff headed by Dr. L.B. Powers, a prominent physician who also served on the school board. Dr. Powers laid the cornerstone of his namesake public school, Dr. L.B. Powers Public School, which operated from 1925 to 1974 across the street from the first hospital site.

In less than six months, the hospital admitted 35 adults and five children. Ms. Emma Elliott of Niagara Falls arrived in October 1913 to become the superintendent nurse. She was recognized for her four years’ of service during WWI with a 1915 Star and held the superintendent position until her retirement in 1941.

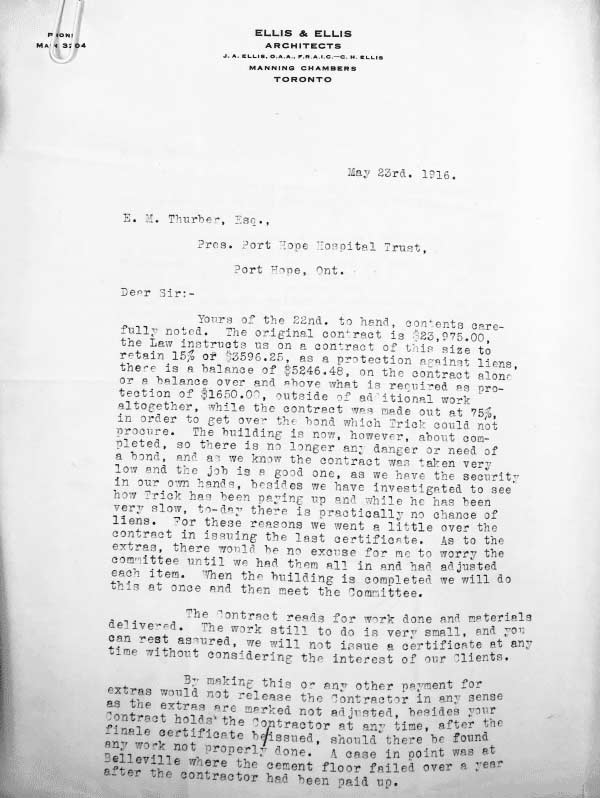

From its opening to October 1913, the hospital cared for 620 patients. Early in 1915, Ellis and Ellis architects in Toronto was hired to prepare plans for the new hospital. The $23,975 J. Trick & Company of Oshawa accepted the tender and, in July, and a building committee was formed to oversee the construction.

A Community Sacrifices To Treat The Men And Women That Fought For Our Freedoms

Early in the winter of 1915, officers of the 136th Battalion asked the hospital to care for ailing soldiers. Surgical cases were cared for in the hospital. The Hospital Board bought a regulation hospital tent for medical cases. Imagine suffering from war trauma and injuries in a tent in winter or caring for these sick people around the clock.

That spring, measles broke out in the tent, and a house was rented on Hope Street as an isolation ward. Orderlies from the tent would take food to the isolation ward that housed 15 patients.

From June to August of 1915, the hospital cared for more than 200 soldiers. About 50 of these soldiers required surgery. The original hospital was planned for nine beds but made room for as many as 15 patients at a time. Nurses would sleep on the floor when necessary. There were hardships and sacrifices made here at home, too, during the war.

Let’s set the scene of the day. Port Hope was a thriving centre of commerce, academia and tourism. The railway was here, and we exported timber, whisky and grain to the U.S. and Europe. Affluent Americans built summer estate homes and cottages along the shore.

By 1914, most of the people in Ontario lived in towns, working in manufacturing jobs instead of farming and primary industries. The war overseas boosted the economy dramatically. Canada saw over $1-billion in war material contracts between 1916 and 1918, 60% of which came from Ontario. Industrial production was concentrated in Toronto and southcentral Ontario, drawing migrants from surrounding areas. Department stores appeared, and leisure activities grew. Women faced the challenges of joining the workplace at a time when domestic service was considered the proper employment.

At first, there was a sense of excitement throughout Ontario and Canada with the opportunity to serve the motherland and play a part in the global conflict. Crowds gathered in communities across Ontario singing “God Save the Queen” and “Rule Britannia.” Patriotic oaths were sworn, and militia headquarters were thronged by thousands of young men ready to enlist. Many were turned away. The enlisted trained for months before heading to France, uncertain of what lay ahead.

Contemporaries called this the Great War because it was more significant than any waged before: more than 59 million troops mobilized, over 8 million died, and over 29 million were injured in a conflict which sharply altered the political and cultural nature of Europe.

Consider this: in 1914, before the outbreak of war, there were only 3,110 men in Canada’s armed forces. Of a population of seven million, more than 640,000 men and 4,500 women, mostly nurses, enlisted.

From Port Hope and area, 476 men of all ranks joined His Majesty’s Canadian Army and crossed the Atlantic to participate in the Great War. While they weren’t treated at the Port Hope Hospital, others just like they were. They fought for the rights and freedom we have today. And so many sacrificed their lives for us.

The names of the 65 men of Port Hope and vicinity who died in the Great War are inscribed on the cenotaph in downtown Memorial Park with the marker text: The Unforgotten Dead.

In 1919, a committee was formed by Rev. James A. Elliott to create a written memorial to those Port Hope men and women who were actively involved in the Great War. Families of those who gave their lives were asked to submit a short biography to be included with their service records, and a photograph to be hung in the town hall. The intention was to remember them as personalities and not just as names on the cenotaph. It was also a record of how the people of a small town joined together to support “their boys” overseas, along with the parents, wives and siblings who were left behind. They lived with the anguish of worry over their loved ones and weathered through shortages, increased workloads and higher taxes.

A public memorial service was held at the Port Hope Armouries on June 29, 1919, where one copy of the written memorial and the photographs were presented to the mayor and town council, and the other copy was given to the library board. Both are preserved at the Port Hope Archives.

The Book of Remembrance is a snapshot of rural Ontario’s contribution to “the war to end all wars” and a lasting tribute to those who paid the price for peace.

As a fundraiser for the Archives to mark the 90th anniversary of the Battle of Vimy Ridge, this Book of Remembrance, reissued in 2007 with updated information, soldiers’ photos, and citizens’ achievements at home in the Imperial Daughters of the Empire, the Empire Tea Room and Port Hope Branch of the Canadian Patriotic Fund. “Letters Home From The Front” that was published in the local newspaper the Port Hope Evening Guide also were included.

Private J.C. Ashman wrote to the Guide on July 26, 1915, from King George’s Hospital in London where he was recuperating from illness after nine days in the wet, cold trenches:

“Just a few lines to let you know I am getting on alright. I guess you will be surprised to hear me, but yesterday I had a lady visitor in to see me, and she gave me the weekly Guide say it was as good as a letter from home and fine to read about the old town…By the way, the lady was a former Port Hoper but has been away now two years, Miss Burham now Mrs. Hodgson. She gave me some beautiful flowers and a cigarette case full of cigarettes and some chocolates, but the fact of being a Port Hoper was as good as a tonic.”

Private J.C. Ashman

Another letter from Private Harold Garbutt from the Front in France telling his mother of life in the trenches on Jan. 29, 1917:

“My Dear Mother, Again I have found a few minutes to write to and to think of those at home. I am seated on the edge of my bed, a rather makeshift affair of chicken wire and scantling, my desk is my knee, and my light a candle. Our billet is a sort of hole in the ground; apparently, it was once the cellar of somebody’s home, but now it is home to three of my comrades and myself. We have a hard time to keep warm, for the weather lately, and even yet, is very cold. There is snow and ice all around, and this on the rough, frozen mud makes very slippery and hard walking…

“Your bundle of Guides also arrived the other day. It really does one good to read the news of the old town; even the advertisements interest me and bring back memories of many a civilian luxury which I had nearly forgotten about. I suppose the skating rink is now going strong and rivalling the old Grand Opera House for the patronage of Port Hope’s pleasure seekers…”

Private Garbutt

Private Garbutt was killed at the Somme 27 days later.

Mr. James Milne of Walton Street received a letter dated Jan. 6, 1918 from Robert W. Masters in France, referring to the death of Mr. Milne’s son, Private Eddie Milne:

“Dear Friend, I have a friend over this evening who chummed with Eddie. He was going to write you but took sick and was in England for some time. We were both up the line the night Eddie was wounded, we saw him down to the dressing station, he was dressed and smiling when we left. We never once thought of it being fatal. We were envying him a nice Blighty. Fred has his hat badge; will send it you if you receive this O.K. We are not sure of your address.

“We were all very sorry to hear about two weeks later of his death, he was a good boy and is missed very much by all the boys. By writing to the Record Office, London, you can get a photo of his grave. We are not very far from it at present, must go down; one other of our boys who was wounded the same night by the shell was buried with him…We are living in hopes that this year will see victory and a lasting peace.”

“How are you all? Have you many apples this year? I would love to have some of those “Duchies.” How are they progressing with the new hospital? Write soon, best love.”

Robert W. Masters

The Aug. 27, 1915 edition of the Port Hope Evening Guide published “A Letter From Egypt” sent to hospital superintendent Miss Elliott from Miss Bowman, a former nurse at the Port Hope Hospital, who went to the frontlines to treat soldiers wounded in battle. The letter was written Aug. 3 at the military hospital in Port Said, a city in northeast Egypt on the coast of the Mediterranean Sea. The naval operations in the Dardanelles Straights earlier in 1915 became land battles supported by the navy that summer to open the sea route to Constantinople.

“My Dear Miss Elliott, We have at last reached our destination and are busy nursing the wounded from the Dardanelles…We are placed in 3 different hospitals, the Government School, the Government Hospital and the New Zealand Hospital. Nearly all the nurses are in the New Zealand hospital with their (N.Z.) own nurses, the majority of the patients are in tents and they say it is very very hard wading through the sand from tent to tent. Miss Papst and I are in the Government Hospital and haven’t the sand to put up with.

“Papst and I each have 1 English orderly and we even have Egyptian doctors. There is an English Dr. in charge but he seldom comes around at night. Just imagine night duty again, I had thought I had enough for a while. The patients are chiefly English soldiers, the nuns have charge of the French and natives…

“Our meals are fair but there are so many things we have been told not to eat. I think after we get accustomed to the country we will get along alright. Two nurses have not been able to go on duty yet. The heat is so trying.

“How are you all? Have you many apples this year? I would love to have some of those “Duchies.” How are they progressing with the new hospital? Write soon, best love.”

Miss Bowman

The Nursing School Set High Standards For Their Pupils

Back at home, the new classic revival style hospital was well underway with the cornerstone laid on October 8, 1915, and the official opening less than seven months later on June 29, 1916. By July 3, the 20-bed hospital was occupied and the original two-storey building immediately became a training school for nurses.

Students attended lectures from the doctors on staff and were trained by Miss Elliott and assistant superintendents. The school graduated 42 nurses to its closing in 1934, including Vera Sawyer, in the last class, who worked at the hospital and became assistant superintendent in 1962.

The pupil nurses worked for $4, $5 and $6 a month for first, second and third years of the three-year training program. The Hospital Board raised the salaries to $8, $9 and $10 a month respectively in 1919. The first graduation ceremony took place in October 1919 with five nurses receiving diplomas.

Miss Elliott, described as a “small, frail-looking woman” was fierce and widely respected. She continued to advocate for higher salaries for nurses and met with the inspector of Training School for Nurses in Toronto, pointing out that too many nurses could not earn a living after three years in training.

In January 1918, an appeal for funds was made for a new west wing. Port Hope residents contributed $3,200 and the Province gave $3,000. However, the Hospital Board reported that the wing would cost $15,000 and work would begin when the government removed restrictions on public improvements. Construction on the wing eventually started in 1928. Meanwhile, A. McMann donated $10,000 for a laundry building, and an x-ray machine was installed in 1924 operated by Miss Elliott.

“Patients were moved to the new hospital on November 6, 1964, and the original hospital later was modified as a nursing home.”

Fast-forward to the 1950s, when the community health needs had outgrown the Ward Street hospital. On April 29, 1960, the Hospital Trust voted unanimously to relocate and build a new hospital at a cost of $1-million. Patients were moved to the new hospital on November 6, 1964, and the original hospital later was modified as a nursing home.

The buildings have been vacant for some time and are in need of repair. Architectural Conservancy of Ontario (ACO) Port Hope has launched a campaign to save this historic hospital that treated our WWI soldiers during and after the war. We want to see the buildings’ owners, Southbridge Care Homes, redevelop the site as the planned long-term care home in keeping with its heritage designation. It can be done and our local heritage architect has provided drawings to make it so.

How can we let these buildings be destroyed?

It is not only a work of craftsmanship and architectural merit, it is a vital part of our town. We have a responsibility to protect this important historical property. Now is the time to stand up and show support. Honour our soldiers, our nurses and doctors – and the residents of Port Hope who rallied to build the first public hospital to serve our town.